This Is Corporate Tax Desertion Taken to a Whole New Level

05 February 16

f you want an example of how bizarre U.S. tax laws can be — and how companies can game the system — look no further than the recently announced deal for Johnson Controls Inc. of Milwaukee to desert our country by combining with a previous corporate deserter, Tyco International PLC.

f you want an example of how bizarre U.S. tax laws can be — and how companies can game the system — look no further than the recently announced deal for Johnson Controls Inc. of Milwaukee to desert our country by combining with a previous corporate deserter, Tyco International PLC.

Tyco is run out of Princeton, N.J., but for tax purposes it is based in Ireland, where the combined Johnson Controls PLC will be based.

This isn’t your standard “corporate inversion,” as polite people call these kinds of tax-avoiding deals. Technically, it’s not even an inversion. Rather, it’s an especially aggressive transaction that, among other things, will let Johnson game the tax system by handing its shareholders about $3.9 billion in cash in order to get tax-free access to $8.1 billion in cash currently held overseas.

You don’t believe that even our absurd tax system will let Johnson PLC do this? Let me take you through the numbers and show you how it works.

A brief aside: Normally, I spare you as many numbers as possible, and don’t use Inc. or PLC after corporate names. But today, I’m departing from that form, because you need to see the details in order to understand the transaction.

Back to the main event. Under our tax laws, if a U.S. company combines with a foreign company (or a nominally foreign company such as Tyco), it can play a variety of tax games, provided that the shareholders of the U.S. company own more than 60 percent but less than

80 percent of the stock in the new, combined company.

However, the company can play far more games — and avoid certain kinds of embarrassment that there’s no space to discuss today — if the shareholders of the U.S. company own more than 50 percent of the combined company but less than 60 percent.

This is where the $3.9 billion in cash comes in.

Under terms of the Johnson-Tyco transaction — which involves Tyco buying Johnson, although Johnson’s management will run the combined company — Tyco will have about 404 million shares outstanding when the deal is consummated. (Tyco has more shares than that, but each current Tyco share will become 0.955 of a Johnson PLC share.)

Johnson has about 647 million shares outstanding. If the companies just combined without playing the cash game I’m about to describe, Johnson holders would own about 61.5 percent of the combined company — 647 million of the 1.051 billion shares.

But Johnson will use the $3.9 billion of cash to buy in about 112 million of its shares. That way, Johnson Inc. holders end up with 535 million Johnson PLC shares, about 57 percent of the 939 million shares that will be outstanding.

When I emailed my math, which is based on public filings, to Johnson spokesman Fraser Engerman, he answered, “Not going to dispute your numbers.”

By being in the more-than-50-less-than-60 percent sweet spot, Johnson PLC can get its hands on its offshore cash directly, instead of having to leap through various hoops as less-aggressive deserters do.

I have no idea why it’s legal for Johnson to buy in a chunk of its shares to make the numbers work — but apparently, it is.

I also have no idea why on Earth more-than-50-less-than-60 percent deals are treated so much more favorably for companies (and unfavorably to those of us who pick up the tab for the taxes they avoid) than more-than-60-less-than-80 percent transactions are.

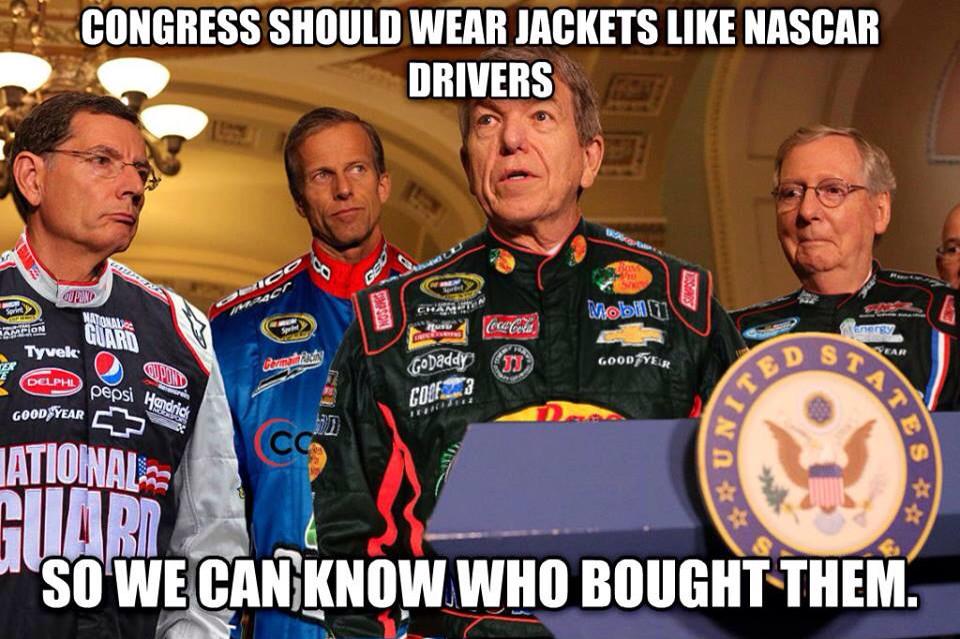

I asked tax expert Ed Kleinbard of the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law about this. He said it’s because of the way Congress wrote Section 7874 of the Internal Revenue Code, which it passed about 10 years ago to try to plug loopholes through which companies squeezed in order to invert.

“Congress drew the 60 percent line when it enacted the statute,” Kleinbard said in an email. “There’s no fundamental economic explanation for that decision. . . . I am not aware of any history that explains why Congress drew the inversion line at 60 percent.”

Pfizer Inc. of New York, which is part of the biggest corporate desertion in history by combining with Allergan PLC of Parsippany, N.J., is also doing a stock buyback and a more-than-50-less-than-60 percent deal. But the arithmetic there isn’t as clear cut as in the Johnson-Tyco deal.

So there you have it. Johnson, a vendor to the taxpayer-rescued U.S. auto industry, repays us by doing not only a desertion but a mega-desertion.

Thanks, guys. If U.S. vehicle makers hit the skids again, maybe Johnson PLC can ask Irish taxpayers for help.

http://readersupportednews.org/news-section2/318-66/35009-this-is-corporate-tax-desertion-taken-to-a-whole-new-level

1 comment:

So Johnson Controls is a bad corporate citizen. I already knew that from my experience with them over employment discrimination. They didn't face legal consequences because the EEOC (and its state equivalent) wouldn’t talk to any witnesses. Both tax laws and the EEOC favor big business, at least in these cases.

Post a Comment