|

| Compelling, ambitious reads you can’t afford to miss. |

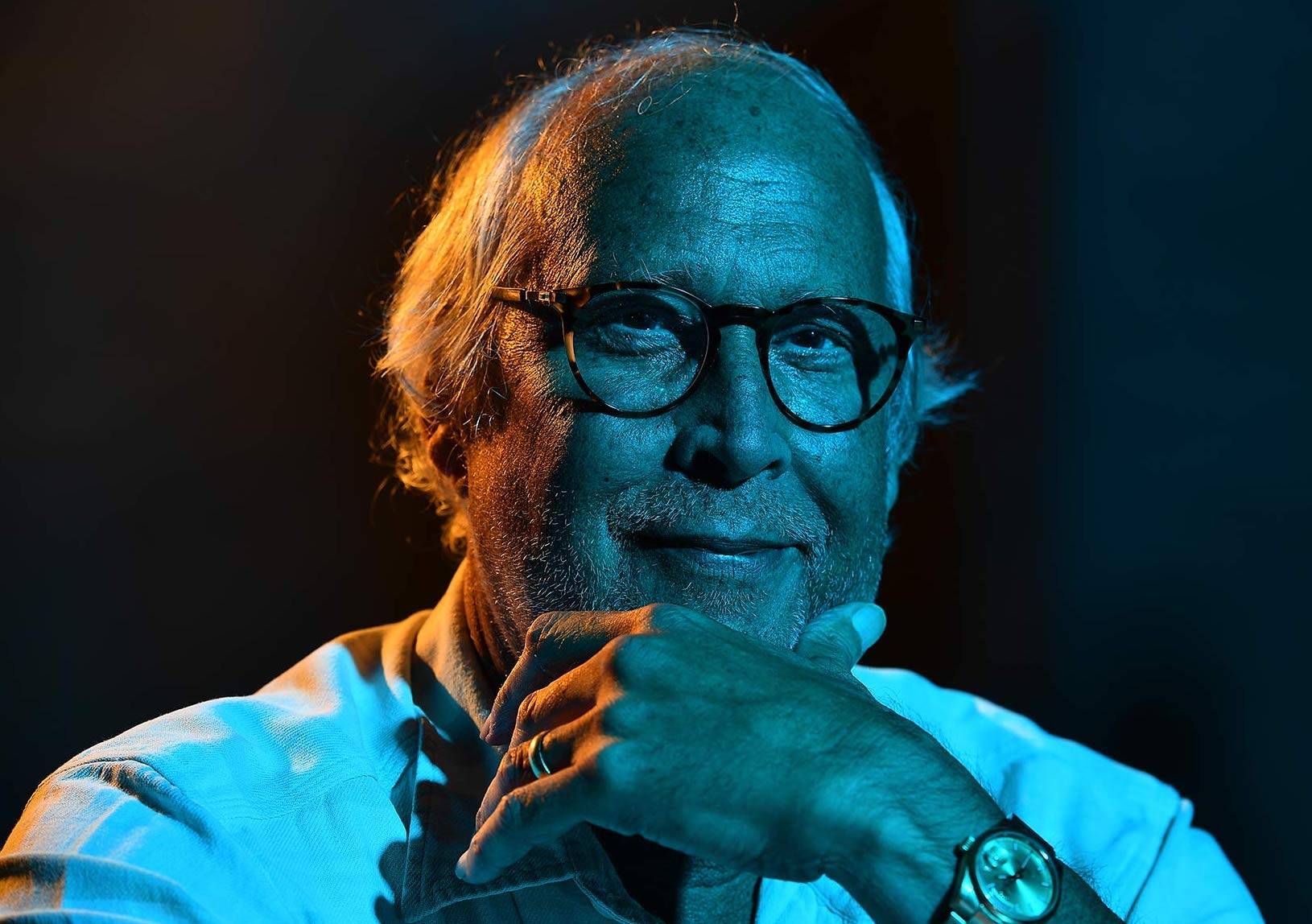

Emma Brown was fully at peace with never publishing the biggest story that she had ever reported.

A few days before President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court, a woman contacted The Post. Her name was Christine Blasey Ford and she claimed that Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her when they were teenagers.

Brown, an investigative reporter, listened to Ford’s story and verified every detail that she could. But there was a catch: Ford wasn’t ready to tell her story to the world and a claim of this magnitude required a source willing to speak on the record.

Brown knew that without Ford’s permission, this story about sexual assault wasn’t hers to tell.

“When you're talking to somebody who's telling you that they've been assaulted, that has to be their choice to come forward,” says Brown. So she waited.

As the summer wore on and Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing began, Brown watched and kept Ford’s explosive claims to herself, carrying the weight of a secret.

“I think there are a lot of stories that reporters” can’t publish, says Brown. “We need verification. Or we may have verification, but it may be off the record,” so it can’t be published.

Just when it appeared that Kavanaugh might head for a confirmation vote without ever being confronted with Ford’s accusation, Ford changed her mind. She was ready to go on the record with her claims.

— T.J. Ortenzi, General Assignment Editor

No comments:

Post a Comment