Why one rape victim won’t support Cianci

I was raped when I was 18. We were kissing, and he asked me to take off my pants. I told him I didn’t want to have sex. He assured me he only wanted to touch me with his hands. But once I took them off, he forced his penis inside me, and restrained me when I tried to push him away.

A woman named Ruth Bandlow tells a similar story of a night in 1966.

According to her story, he said he knew a friend of hers. Wouldn’t she come home and have a drink with him?

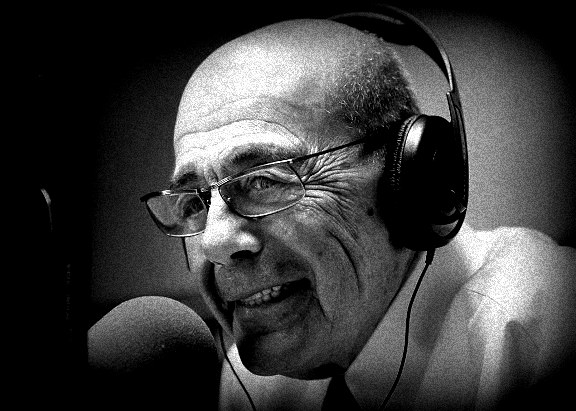

Both parties agree that Bandlow accompanied Cianci home that night. In a New York Times interview, Cianci called the encounter a “togetherness, a one-night stand kind of thing.”

Bandlow’s version, as recounted in this court filing and Mike Stanton’s book “Prince of Providence”, goes a little differently:

When they arrived he offered her a drink—a rum and coke. It quickly made her feel ill. She recalls deflecting his attempts to kiss her and blacking out. When she awoke, he was on top of her. He held a gun to her head and told her not to scream or struggle.

“Look out the window—there’s a ravine there,” Cianci said to Bandlow, according to Stanton’s book. “I could throw your body down there, and no one would ever find you.” After that, she stopped struggling and he raped her.

The court document reveals that when police searched Cianci’s house, they recovered sheets with blood on them and the pistol Bandlow described. Both Bandlow and Cianci agreed to take a lie-detector test. Bandlow passed hers. Cianci failed three times.

The investigators were convinced. It was “one of the most clear cut cases of rape he had ever processed,” said Joe Wilamovsky, an expert working on the forensic investigation of the case, according to the court filing. Stanton quotes Harold Block, the primary officer on the case: “We thought we had everything….We thought we had enough to convict him.”

But Cianci was never charged. Bandlow withdrew her complaint and in quick succession money changed hands. They both admitted this in court documents– $3,000 according to Bandlow. The public never knew of the rape case until July, 1978, while he was in the midst of a campaign for reelection as mayor of Providence. The publication New Times released a detailed and damning article about the case. According to a UPI article from July 10, 1978, Cianci called it “character assassination” and filed a libel suit. He still won the election.

Since then he has been asked about his story many times and discrepancies occasionally appear. During discovery for his suit, when Cianci was asked about the three failed polygraphs described in the police report, he said he only took one and was never told the results. In later testimony for the suit, he said the technician had told him he had nothing to worry about. The story changed again in June, 2013, when he told the New York Times, “I never took three lie-detector tests. I never took any lie-detector test.” But that is not what’s reported in a short article in the Milwaukee Sentinel from March 5, 1966, which says both parties agreed to take a polygraph, according to what Stanton wrote in his book.

There are other unnerving stories in Cianci’s public history when it comes to his treatment of women.

Sheila Cianci, his ex-wife, told her friend Raymond DeLeo about incidents from her marriage. An excerpt from Stanton’s book in the Providence Journal says, she said she was afraid to file for divorce due to his frequent threats: She recalls one instance when he threatened to throw her over the second-floor banister. And she may have had reason to believe he was serious: DeLeo testified under oath that Mrs. Cianci said her husband had once tried to strangle her. If what Mrs. Cianci recounts is true, she was facing severe emotional and physical abuse. She also said she had had to secretly take money from his jacket pockets because he was restricting her access to funds, a form of control known as financial abuse.

Wendy Materna, another long-term partner of Cianci’s, told Stanton she “suffered his verbal abuse.” He was frequently unfaithful to her, she says, and notes that when she went out, she was never alone: “Buddy’s baby-sitters” were everywhere she went. When she decided to leave Cianci, she explained to her mother that he’d “been making [her] cry for nine years.” His reaction, she says, was to threaten her new boyfriend. Stanton writes that he “threatened to plant drugs on her boyfriend and tip off the police … she had heard Cianci say the same thing many times before about political rivals or anyone else who angered him.”

Cianci also tapped her phone, sent his associates to warn her to “behave,” and made repeated appeals to her mother, according to Stanton. Cianci and Materna fell out of touch for a long time, but they have now reconciled. When a Boston Magazine reporter asked her why, her words were not of love or forgiveness; she simply said, “He was the devil I knew.”

According to a Centers for Disease Control report from last month, as many as two thirds of American women have experienced sexual violence and according to the Rape and Incest National Network, only 3 out of 100 perpetrators of sexual violence spend even one night incarcerated. Part of the reason for these statistics is because many victims—perhaps as many as 60%–never bring their assaults to the authorities out of fear or shame. But the real problem is that no one believes them. Even when a rape is reported, according to RAINN, there’s a 75% chance that the rapist won’t be arrested. On our hands we have a national pandemic of the sickest form of violence a human can perpetrate.

And Providence is no exception. A representative of Day One, the only organization in Rhode Island that deals with sexual violence in the community, told me that overall in Rhode Island the climate is improving and people are becoming more aware of the problem. But that awareness is tenuous and needs to be nurtured, and it especially needs a helping hand in Providence: While the Day One representative was able to name a number of initiatives on the state level to improve awareness of and response to sexual violence, when I asked about initiatives taking place in Providence, perhaps by City Hall or in the schools, she was not able to name any. An ER nurse specially trained to do rape kits from Women and Infants Hospital told me that many victims who come in for a rape kit are not believed by the police. Providence clearly needs to take action in reducing sexual violence in our community. But can a man like Buddy Cianci, whose partners have alleged rape and abuse, be the leader we need to help solve these problems?

The CDC report emphasizes the need for prevention in solving this problem, particularly by educating children and teens about healthy relationships using thorough, ongoing programs, both in the community and in schools. Providence currently lacks these programs. Would Cianci take the necessary efforts to establish them seriously?

The CDC also suggests increasing access to the proper services for victims. Day One reports positive interactions with the Providence Police, but based on the W&I nurse’s report, they still need better training in responding to sex crimes. Day One has also been trying to expand their services, but they could use more funds. There is a large number of victims who need their services, especially in Providence, where rates of sexual violence are very high, partly due to human trafficking. Peg Langhammer, Executive Director of Day One, says in a recent video that “there hasn’t been a coordinated community response to this issue [of child sex trafficking].” It is Day One, not City Hall, who are taking the initiative in trying to fill this need. Is someone like Cianci going to take the need for greater efforts on the part of City Hall seriously? Can a man who is himself prone to violence effectively campaign to reduce violence?

My rapist walks free, as does the man Ruth Bandlow accused. When Nancy Laffey, a reporter for Milwaukee’s Channel 12, interviewed Bandlow in 1977, she showed her Cianci’s yearbook photo. She burst into tears, saying, “I can’t even look at him.”

I often think of her now as I walk or drive around the city, and I see sign after sign with his face and his name looming over the streets and sidewalks. To endorse a man is to forgive his past actions. Those who post the Cianci signs are forgiving what police considered strong evidence of a rape and stories from partners who said they were in physical and emotional pain living with him–not to mention a conviction for kidnapping and torture.

With their signs, they are saying none of that matters. The signs, and Buddy Cianci’s lead in mayoral-campaign polls, are symbols of the apathy the public feels towards rape victims. Peg Langhammer of Day One says that “it takes an entire community to effectively respond to this issue.” Cianci won’t respond. His supporters who hang his signs are declaring they won’t either.

Rape victims hide in plain sight. They are the men, women and children all around you; they are people you love living in silence. Ninety-seven percent of us walk around knowing our perpetrator is still out there. When we see those signs, we hear their voice in our heads, reminding us of what we fear most: “You don’t matter. You are nothing. I have all the power and I always will.”

Electing Cianci mayor, giving him power over our city once again, will make our fear a reality.

Sources:

(Note: all material attributed to “Buddy, we hardly knew ya” from the July 24, 1978 issue of New Times is taken from secondary sources, as the original article is not available for free online.)

No comments:

Post a Comment