|

‘Now We Know Oil Is More Toxic Than We Thought’ - CounterSpin interview with Riki Ott on Exxon Valdez spill

view post on FAIR.org

Janine Jackson interviewed Riki Ott about looking back on the Exxon Valdez oil spill for the March 27, 2009, episode of CounterSpin—an interview that was reaired for the June 14, 2019, show. This is a lightly edited transcript.

MP3 Link

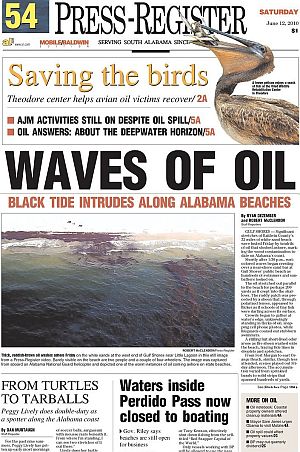

Mobile Press-Register (6/12/10)

Janine Jackson: The BP Gulf of Mexico spill is still ongoing, really; 2019 reports describe lingering health impacts on cleanup workers, for instance.

But in June of 2010, the spill was front-page news. And that was about the time when BP hired regular CNN commentators Alex Castellanos and Hilary Rosen as lobbyists. Rosen lost her job at the Huffington Post, where she’d been Washington editor-at-large, but they both kept their jobs as CNN pundits. It’s OK, CNN explained, because

both Alex and Hillary are political contributors, used to comment on political issues. They are not being used to discuss the oil disaster story.

That sort of malfeasance never seems to play a role in corporate media “looks back” or “lessons learned” at catastrophic events like major oil spills. The press was part of the story when CounterSpin spoke with Riki Ott in 2009. Riki Ott is an activist and marine biologist, and author of Not One Drop: Betrayal and Courage in the Wake of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. When I spoke to her in 2009, my first question was to what extent the Exxon Valdez was a live story, and not one 20 years old.

Riki Ott: We still do not have the herring back in Prince William Sound. Herring are a foundational species in Prince William Sound; they’re the forage fish that whales, seals, sea lions, sea birds all rely on. Realistically. without herring, Prince William Sound cannot recover. So we are waiting for the herring to recover, and they collapsed, really, in 1989, when the young of the year did not survive their oil bath. And four years later, when those fish should have become adults, they weren’t there. And that’s when the population crashed.

We also rely on herring for our economy. So there are still fishermen, to this day, the herring fishermen—it’s closed indefinitely—they are out of that line of work. We are still incurring long-term harm from something that happened 20 years ago now. So that’s sort of the environmental and economic side.

But there’s more. And this is where it’s in the interest of all Americans to really understand what happened in our Supreme Court decision, back in June of 2008.

The Supreme Court decided to break the link between punishment and profit; the jury had decided that it would really take a link between punishment and profit to punish a corporation. This big $5 billion was one year’s net profit in 1994. The Supreme Court decided, “No, punishment should instead be linked to damages.”

As I’ve just explained, we were only compensated for short-term damages. But this set precedent, now, this capping of punitive damages to a one-to-one ratio of punitive to compensatory, this makes every community in America vulnerable to corporate greed, and the most—let’s stay with Exxon Valdez — if $5 billion had indeed been punishment, then Exxon should have been the first company to double-hull its tanker fleet and make them safer, rather than the last.

And what we see now is Exxon, of the top 10 oil shippers, Exxon has more single-hull tankers afloat in the world’s oceans than the other nine companies combined, all to earn its shareholders an extra penny a year on their stocks.

JJ: On that hulling note, I was interested in the New York Times editorial that declared matter of factly that supertankers are now double-hulled because of the Valdez. They made it sound as though policies flowed sort of naturally and immediately from the disaster. And that’s not at all how it went. I mean, you’ve just indicated that the company that ought to have gone straight to double-hulling, Exxon, is lagging, and it’s been a lot of activism that has made the other companies take the steps that they’ve had, hasn’t it?

RO: It’s only been activism. Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 that requires double-hull tankers by the year 2015. That essentially gave these big, powerful oil companies 25 years to try to weaken and reduce that standard. And try they have. And the only thing that has kept that standard, there were two things: One was citizen oversight, citizen activism, also required by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. It pushed back each end-run that the oil companies tried, four times. And, finally, the Prestige and the Ericka oil spills in Spain and France sealed the deal, when the international community just got outraged and demanded double-hull tankers by the year 2012. The fleet is largely shifting; over and again, it’s been Exxon who’s the most recalcitrant company of all.

JJ: So if the theme is “lessons learned,” I guess maybe the most important lessons have to do with activism. Let me ask you: You’ve watched media operate now in Alaska and nationally for decades now. And you describe a process that I’ve heard you call “media capture.” What do you mean by that? How does that work?

Riki Ott: “I was shocked to see how easily Exxon could make its story the dominant story.”

RO: I was shocked to see how easily these big oil companies, in this case Exxon, could make its story the dominant story in the news, and this has actually driven me to write two books, trying to correct 20 years of wrong-headedness by the media.

The lies started on day one. I landed in Valdez, and within 12 hours of the grounding, I was down with the federal scientists, the NOAA people. And they were estimating the size of the spill, based on computer modeling. And it was between 11 (low-end estimate) million gallons to 38 million gallons. Exxon captured the low-end number.

When the press started asking, I was in the room, watching. Who validated that? Who verified that? Exxon spokesperson Frank Iarossi kind of threw out that “alcohol may have been involved” quote. And just like that, I watched the national media switch tracks like a railroad, and it became 11 million gallons ever since that day. The reason that’s important, and I knew it would be, was because penalties are based on spill volume, right, and correction measured based on spill volume.

So what do we have in Alaska right now? We are prepared to respond to an “Exxon Valdez-size” oil spill, which means three times less than what really spilled.

JJ: …than what actually happened. Well, that 11 million —or even 10.8, is what is on the record—that’s what’s being reported in the anniversary coverage.

In 1989, FAIR did a study of the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, then as now considered among the most serious news programs. And between February and August of that year, they did seven segments on the Valdez spill, not one of which included an environmentalist. Debate on that show was illustrated by the then-chairman of Exxon and the governor of Alaska, who sat down to have a cozy conversation, in which the governor of Alaska said that the chairman of Exxon was being far “too heavy on his own company.”

So we found that a kind of top-down bias in media—talking to just the corporate officials and government officials — really left out what were the key perspectives at the time.

RO: And, you know, it’s not just at the time; that’s another huge problem, is that these stories evolve. The killing did not stop in 1989. Where was the media to cover the 1992 pink salmon run collapse, the 1993 pink salmon run collapse?I mean, we actually held a blockade of the Valdez Narrows, held up oil tanker traffic, that brought in the media and attention, and it started the ecosystem studies, which took 10 years to complete. And now we know that oil is more toxic than we thought.

And where is the news on this? This should be tied into the debates right now on global climate crisis. Do we need to get off oil, not only for the sake of the planet, but also that this stuff is much more toxic than we thought in the 1970s, when we passed the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act? We’re talking 1 percent of a child’s lung capacity for every one year of their life, just by breathing urban air that the federal government regulates as safe and is not. Bush administration standards are now being challenged by Obama. And this is the fine soot standard, this is polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, the fraction of oil that we now know causes long-term harm, in wildlife and in people.

Not One Drop: Betrayal and Courage in the Wake of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, by Riki Ott

JJ: Let me ask you, how then do we sanction corporations that commit acts of devastation like that of the Valdez?

RO: I would like to see us take a good look at what we’ve done with these big corporations. We have given them, through the Supreme Court, rights that were only intended for humans. We have created, literally, a monster in our midst; we have created a way to consolidate wealth and power and privilege that is destroying our ability to hold these companies accountable.

So I am advocating coalescing this sort of unrest across the nation, that we saw starting with WTO protests in Seattle, into a citizen movement, and to pass the 28th amendment to the Constitution, stripping corporations of human rights. This gets to the heart of campaign abuse, the legal system abuse, lack of enforcement of our law officials, and actually strikes at the heart of globalization.

JJ: That was Riki Ott, activist, marine biologist and author of, among other titles, Not One Drop: Betrayal and Courage in the Wake of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. You can catch up with her work at her website RikiOtt.com

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment