Please don't call American NAZIS... NAZIS!

Facebook Fascist Gremlins don't approve!

And I'm blogging it!

This post got Jim Wright of Stonekettle Station fame banned from his FB account.

So I am reposting it.

BEGIN QUOTE

I don't envy Mike Godwin, his law is getting a hell of a workout

I don't envy Mike Godwin, his law is getting a hell of a workout

I've got hundreds of angry messages here telling me to stop calling Trump supporters fascists.

And I would, except for the part where I keep running into ACTUAL FUCKING NAZIS.

And I would, except for the part where I keep running into ACTUAL FUCKING NAZIS.

This guy for example. He's upset at my "brand of profanity" (I used the term "ball-gargling" in reference to Sean Hannity. My apologies, but as a retired military officer and professional writer when I see somebody gargling balls I'm required by law to use the technical term. I digress), but sees nothing profane about naming himself after an infamous French collaborator and member of the Waffen SS. Not to mention his "heroes" are literally a list of fascists, fascist murderers who became the actual Nazi party, and white supremacists.

And then there's "Jewry." Just right there, in a sentence, like you know that's something people who aren't Nazis do.

So again, you don't want to be called a Nazi?

Then stop hanging out with actual Nazis. Just stop it. Stop it. Stop it.

Stop hanging out with Nazis. Don't be polite to Nazis. Don't think that the First Amendment means you have to be respectful of Nazis. Don't pretend Nazis have a valid point of view. They're Nazis.

Stop standing next to Nazis.

Stop acting like Nazis.

Stop cheering Nazis.

Stop voting for the people Nazis vote for.

They're fucking NAZIS. You don't have to be polite to them. It's okay to hate them. They're fucking NAZIS.

And for the love of Dread Cthulhu, stop using the word "Jewry."

END QUOTE

END QUOTE

FOOTNOTE: GODWIN'S LAW:

Mike Godwin's Law: from counter-memes to countering the FBI

The cyberspace rights attorney and creator of a classic internet adage reflects on liberties, whisky and rock climbing alone

Back in 1990 – before users referred to the internet as the World Wide Web and a negligible number of mavericks held discussions on Usenet newsgroups, the Well, and Bulletin board systems (BBS) – Mike Godwin, then an Austin law student, created one of the first internet memes.

It was called "Godwin's Law of Nazi Analogies", and the assertion went like this:

"As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one."

After he seeded Godwin's Law within various BBS threads, it caught on with ease, even morphing into different versions of the same basic idea, much like the ubiquitous "condescending Willy Wonka", or, aptly, "Hitler's reactions to things". Now, anyone who wields "Godwin's Law" in any forum knows they're talking about pretty much the same thing, regardless of context.

It was a rhetorical term, a counter-meme for the projective "meme" (in an oldersense) already commonly used both online and off. Godwin meant Godwin's Law to get people to think a little harder about history, and recognize that Nazi crimes are not merely "handy tropes" for "net.blowhards" railing against abortion or general censorship. This excludes actually defensible comparisons, like those of two different superpower's warring tactics – and of course, humor: Seinfeld's "Soup Nazi" is deliberately extreme. "Feminazi", not so much.

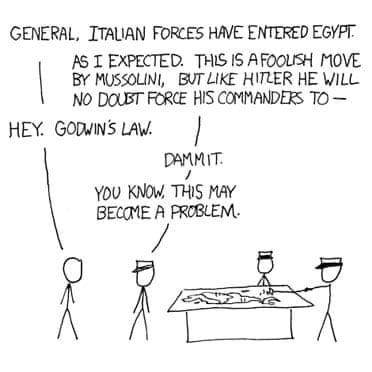

Randall Munroe’s webcomic xkcd putting the Law in action. Photo: xkcd.com/261/

Eventually, even Glenn Greenwald had to defend his essay comparing propoganda tactics employed by the US government in its Iraq invasion to those used by the Nazis. Critics cited the law – a "distorted" version – and as the online debate gathered momentum, even Godwin himself appeared in the comments section of Greenwald's articles, explaining that his law sought to "discourage frivolous, but not substantive, Nazi analogies and comparisons". Using words delicately, in other words, means that when history is actually repeating itself, we'll be able to recognize it and then give it a name that everyone can understand.

Godwin was hired right out of law school by the Electronic Frontier Foundation – a non-profit umbrella of legal counsel that seeks to extend the constitution's protections into cyberspace. He first worked on Steve Jackson Games, Inc v United States Secret Service, a wrongful raid of the company's headquarters in response to an employee's digital distribution of a document that was public physically.

"I knew this was a first amendment case, and that the secret service had overstepped its bounds, due generally to fear and suspicion of new computer media."

Offline, there's (usually) a general expectation that we'll only be physically followed or frisked if we are suspected of doing something wrong – but with one new technology after another, that expectation narrows. For example, as phone companies collect on our usage, by necessity, federal agencies often act as though collecting that information is not actual intrusion. With new technologies, it not only becomes easier and cheaper for government agencies to spy, but sometimes the law in cyberspace is treated as up to interpretation.

When the FBI demanded Wikipedia remove the agency's official seal from its corresponding article, Godwin was general counsel to the Wikimedia Foundation, and wrote back:

"The Bureau's reading of [Section 701: Official badges, identification cards, other insignia] is both idiosyncratic … and, more importantly, incorrect."

Godwin knew that the FBI's demand was a fraudulent prohibition of seal usage by its general counsel:

"If I had sent a dreadfully earnest letter, they would have at best disagreed or, worse, sued me and the Wikimedia Foundation. Perhaps they would have won, and shaped future policy."

The real goal of his catty, three-page response, he says, was to embarrass a bureaucratic agency with humor – he pointed out its redaction of vital words defining the proper usage of Section 701 in its accusatory letter, and how it led the FBI to call Wikipedia's use of its seal "problematic".

"I hope you will agree that the adjective 'problematic,' even if it were truly applicable here, is not semantically identical to 'unlawful,'" Godwin wrote at the time. It worked. Over 150 newspapers covered the exchange, and the New York Times published the FBI's seal along with its own coverage. Online.

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2013/oct/29/mike-godwin-nazi-analogies-meme-update

No comments:

Post a Comment