Dear Friend,

Dr Andrew Glikson warns that attempts at CO2 down-draw (sequestration), if urgently applied on a global scale, may conceivably be able to slow down further warming. This article refers to natural methane reservoirs and human induced methane emissions, indicating that, once temperatures supersede a critical level, a further rise in methane release would result regardless of restrictions of emissions.

War reporter turned Climate journalist Dahr Jamail breaks down talking about climate change

Kindly support honest journalism to survive. https://countercurrents.org/subscription/

If you think the contents of this news letter are critical for the dignified living and survival of humanity and other species on earth, please forward it to your friends and spread the word. It's time for humanity to come together as one family! You can subscribe to our news letter here http://www.countercurrents.org/news-letter/.

In Solidarity

Binu Mathew

Editor

Countercurrents.org

Global

warming and the habitability of planet Earth

by Dr Andrew Glikson

Attempts at CO2 down-draw (sequestration), if urgently applied on a global scale, may conceivably be able to slow down further warming. This article refers to natural methane reservoirs and human induced methane emissions, indicating that, once temperatures supersede a critical level, a further rise in methane release would result regardless of restrictions of emissions.

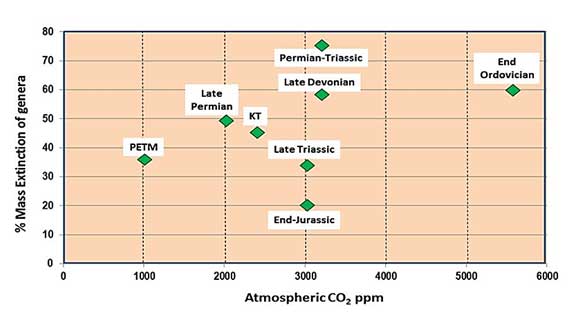

Carbon, the essential element underpinning photosynthesis and life, is transformed into toxic substances in the remnants of plants and organisms buried in sediments. Once released to the atmosphere (Fig. 1) in the form of CO2, CO and methane, in large quantities these gases become lethal and have been responsible for mass extinctions of species (Fig. 2).

Given amplifying feedbacks from land and oceans triggered by rising temperatures, the concept of an upper limit of warming determined by limitation on carbon emissions alone is unlikely, since, under a rising high greenhouse gas concentration, amplifying feedbacks triggered by methane release (Fig. 1), bushfires, warming oceans and loss of reflectivity of melting ice, temperatures would keep rising. Recent findings show that warmer ocean water is melting crystallized methane and releasing it into the sediment and waters off the coast of Washington state, at levels that reach the same amount of methane from the Deepwater Horizon blowout.

Attempts at CO2 down-draw (sequestration), if urgently applied on a global scale, may conceivably be able to slow down further warming. This article refers to natural methane reservoirs and human induced methane emissions, indicating that, once temperatures supersede a critical level, a further rise in methane release would result regardless of restrictions of emissions.

According to Kelley (2003) a planetary “runaway greenhouse event” may be triggered when a planet overheats due to absorption of more solar energy than it can give off to retain equilibrium. As a result the oceans may boil filling its atmosphere with steam, which leaves the planet uninhabitable, as Venus is now. Planetary geologists think there is good evidence that Venus was the victim of a runaway greenhouse effect which turned the planet into the boiling hell we see today. According to Hansen (2012)“if we burn all reserves of oil, gas, and coal, there’s a substantial chance that we will initiate the runaway greenhouse”. In a critical review of the theory of the runaway greenhouse syndrome Goldblatt and Watson (2012) state: “We cannot therefore completely rule out the possibility that human actions might cause a transition, if not to full runaway, then at least to a much warmer climate state than the present one.”

Fig 1. A methane explosion crater in the Yamal region of Siberia

The concentration of fossil carbon deposits in the form of coal, oil, natural gas, coal seam gas, permafrost methane, ice clathrates, shale oil, and oil sands, once released to the atmosphere in large quantities, generates powerful feedbacks from land and ocean. This includes further release of greenhouse gases, warming oceans, loss of reflectivity of melting ice, and bushfires, pushing temperatures further upward. With greenhouse gas concentration rising at a rate of 2–3 parts per million (ppm) per year[1] and the Earth heating-up by 0.98oC since 1936, the ultimate consequences of this trend belong to the unthinkable.

Fig. 2Relations between CO2 levels in the atmosphere and mass extinctions of genera. Data cited from Royer et al. 2002 and from Keller 2005 and Wignall and Twitchett 2002

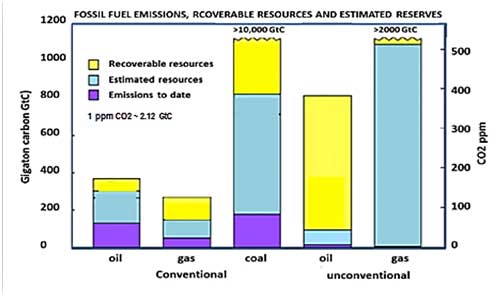

By 2012 total emissions are estimated to have reached 384 GtC, with an annual amount of 41.5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2018. According to the IPCC (2013) no more than 275 GtC of the world’s reserves of fossil fuels of 746 GtC can be emitted if global temperature rise is to be restricted to 2oC above pre-industrial temperatures, an impossible target since amplifying carbon feedbacks would push temperatures upwards.

According to Hansen et al. (2013) recoverable fossil fuel reserves include ~120 GtC gas, ~80 GtC oil, >10,000 GtC coal, >2000 GtC unconventional gas, ~700 GtC unconventional oil, totaling ~13,000 GtC (Fig. 3). According to Heede and Oreskes (2016)global reserves of oil (~171 GtC), natural gas (~95) and coal (479 GtC) totaling 746 GtC, are below Hansen et al.’s estimates.

Fig 3. Estimates suggest the possibility of near-or above 13,000 GtC of fossil fuel reserves (Hansen et al. 2013).

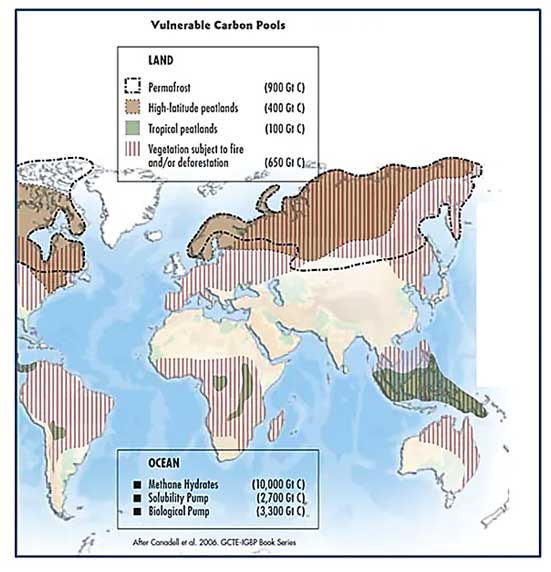

The amount of unstable methane deposits in permafrost (Fig. 4) and methane hydrates (clathrates) in ocean sediments (Fig. 5) is of a similar order of magnitude as the amount of fossil fuel reserves. This includes methane hydrates in sediments (~10,000 GtC), solubility and biological pump (~6000 GtC), Permafrost methane (~900 GtC), tropical peatlands and vulnerable vegetation (~750 GtC) (Fig. 4). Unoxidized metastable deposits of methane and methane hydrates, accumulated during the Pleistocene glacial-interglacial cycles and vulnerable to temperature rise, are already leaking as indicated by atmospheric concentration which have risen from 1988 (~1700 ppb CH4 ) to 2019 (~1860 ppb CH4 ) at a rate of ~5.2 ppb/year, which for radiative equivalent of X25CO2 reached more than 40 ppm CO2-equivalent.

Fig 4.Vulnerable carbon sinks. ( a ) Land permafrost ~ 600 GtC; High-latitude peatlands ~ 400 GtC; tropical peatlands ~100 GtC; vegetation subject to fire and/or deforestation ~ 650 GtC; ( b ) Oceans methane hydrates ~10,000 GtC;Solubility pump ~2700 GtC; Biological pump ~3300 GtC; total ~17,750 GtC

Fig 5a. Global distribution of methane hydrate deposits on the ocean floor.

Fig. 5b plumes of methane bubbling to the surface of the Arctic Ocean.

Fig 5c. Frozen methane bubbles at Abraham Lake, Alberta

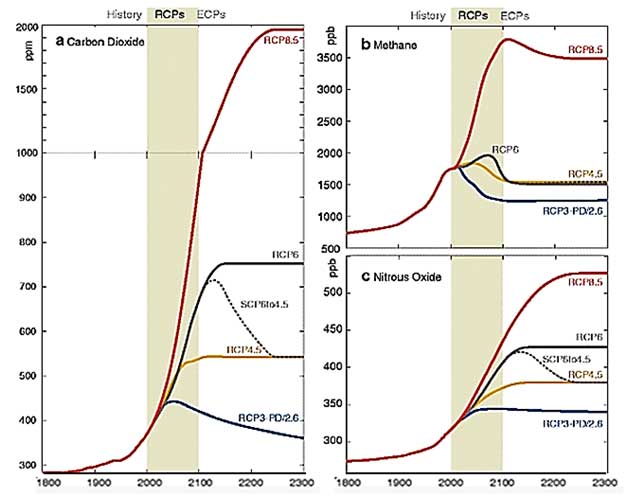

Meinshausen et al. (2011) estimated global-mean surface temperature increases, applying a climate sensitivity of 3°C per doubling of CO2, affecting by 2100 a temperature rise between 1.5°C to 4.5°C relative to pre-industrial levels. By 2300, under constant emissions, CO2 concentration would rise to ~2000 ppm, methane to 3.5 ppm and nitrous oxide to 0.52 ppm (Fig. 6). Amplifying feedbacks are taken into account, but the effects of tipping points and of cold ice-melt pools formed in the oceans near Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets are unclear.

Fig 6.GHG concentrations recommended for the CMIP5 (Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project) to the year 2300. Shown are: (a) atmospheric CO2; (b) methane; (c) nitrous oxide. Methane levels of 3500 ppb = 3.5 ppm x25forcing = 87.5 ppm CO2equivalent; N2O of 500 ppb = 0.5 ppm x298forcing = 149 ppm CO2equivalent.

Given the estimated total of exploitable hydrocarbon resources (~13.000 GtC) and of unstable methane deposits (~17,750 GtC), the amount released under different future climate conditions is subject to estimates:

A. Assuming mean global temperature of +2oC (above pre-industrial), with allowance made for the masking effects of sulphur aerosols, the combustion of ~2 percent of the fossil fuel reserves (13,000 GtC), i.e. ~260 GtC, would raise CO2 concentration by ~130 ppm (100 GtC = 50 ppm CO2) ( 3). Combustion of ~5 percent of the fossil fuel reserve would raise CO2 concentration by ~325 ppm.

B. Under +2oC above pre-industrial, release of CO2 from fires and other feedback effects such as melting of permafrost and release of methane would raise atmospheric carbon by at least 1 percent of natural unstable carbon deposits(~17,750 GtC).

C. The flow of ice melt water from Greenland and Antarctica into the oceans would create large regions of cold water capable of absorption of atmospheric CO2.

According to the Hansen et al. (2013)“If we burn all reserves of oil, gas, and coal, there’s a substantial chance that we will initiate the runaway greenhouse. If we also burn the tar sands and tar shale, I believe the Venus syndrome is a dead certainty”. Stephen Hawking (2017) appears to agree with Hansen’s warning, stating: “if the US pulls out of the Paris climate agreement it may lead to runaway global warming, eventually turning Earth’s atmosphere into something resembling Venus”. Goldblatt and Watson (2012) wrote “The ultimate climate emergency is a ‘runaway greenhouse’: a hot and water-vapor-rich atmosphere limits the emission of thermal radiation to space, causing runaway warming … This would evaporate the entire ocean and exterminate all planetary life … We cannot therefore completely rule out the possibility that human actions might cause a transition, if not to full runaway, then at least to a much warmer climate state than the present one … However, our understanding of the dynamics, thermodynamics, radiative transfer and cloud physics of hot and steamy atmospheres is weak.”

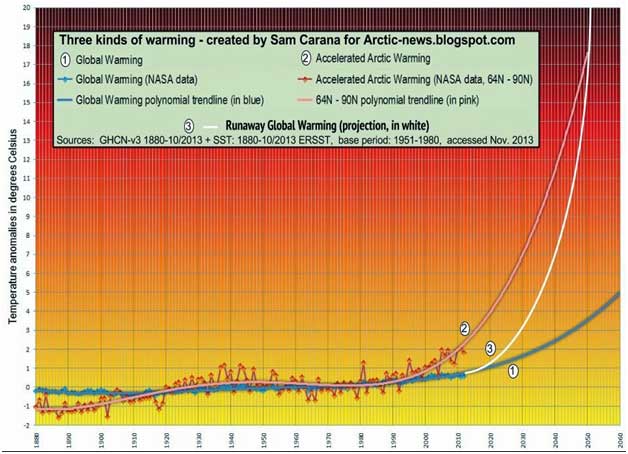

An analysis by Carana (2013) suggests accelerated release of methane from permafrost and methane hydrates (clathrates) could trigger runaway global warming (Fig. 7). A polynomial trend for the Arctic shows temperature anomalies of +4°C by 2020, +7°C by 2030 and +11°C by 2040, threatening major feedbacks, further albedo changes and methane releases leading to global temperature anomalies of 20°C+ by 2050.

Fig 7.A polynomial[2] trend line points at global temperature anomalies (Carana 2013).

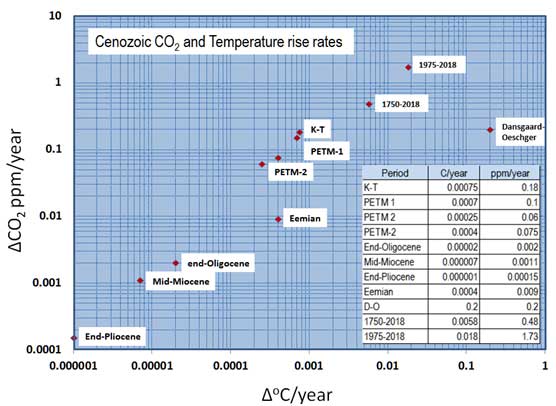

The magnitude of a runaway greenhouse effect is constrained by evidence from the geological record. For example, the 55 million years-old PETM event (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum), lasting for about 100,000 years, driven by high CO2 level of 1700 ppm, does not appear to have triggered a runaway greenhouse process. The PETM is attributed to 13C-depleted methane (Zeebe et al. 2009), reaching 5 – 8oC and leading to a mass extinction of 35-50% of benthic foraminifera. By sharp contrast the current Anthropocene hyperthermal event, commencing with the industrial age and re-accelerating since about 1975, constitutes a temporally abrupt development exceeding the rate of geological hyperthermal events (Fig. 8), a rate which does not allow biological adaptation and thereby enhances a mass extinction of species (Barnosky et al. 2011).

Fig 8. A comparison of Cenozoic CO2 rise rates and temperaturerise rates, highlighting the extreme rise rates in the Anthropocene.

[1]; October 2018: 406.00 ppm;October 2019: 408.53 ppm

[2] A polynomial function is a function such as a quadratic, a cubic, a quartic, and so on, involving only non-negative integer powers of x.

Andrew Glikson, Earth and climate scientist, Australian National University, geospec@iinet.net.au

Dealing With Climate PTSD

by Dahr Jamail

War reporter turned Climate journalist Dahr Jamail breaks down talking about climate change

Recently, I was in Homer, Alaska, to talk about my book The End of Ice. Seconds after I had thanked those who brought me to the small University of Alaska campus there, overwhelmed with some mix of sadness, love, and grief about my adopted state — and the planet generally — I wept.

I tried to speak but could only apologize and take a few moments to collect myself. It’s challenging for me, even now, to explain the wash of emotions and thoughts that suddenly swept over me as I stood at that podium on a warm, windy, rainy night on the southern Kenai Peninsula among a group ready to learn more about what was happening to our beloved Earth.

“Sorry for that,” I finally said after a few more breaths, as my voice cracked with emotion, “but I know you’ll understand. You live in this state and you know as well as I do that once Alaska gets in your blood, it stays there. And I love this place with all my heart.” Most of the listeners in that room were already nodding and at least one person had begun to cry.

I lived in Alaska for a decade, starting in 1996, and it’s been in my blood since the year before that when I first laid eyes on Denali National Park and the spectacular Alaska Range. In fact, five of the nine chapters of my new book are set in Alaska and its mournful title is a kind of bow to my abiding love for this country’s northernmost state. That moment in 1995 when the clouds literally parted to reveal Denali’s lofty summit and its spectacular spread of glaciers proved to be love at first sight. In fact, most summers thereafter I would visit that range as well as others in Alaska, volcanoes in Mexico, the Karakorum Himalaya of South Asia, or the South American Andes.

Then, in the summer of 2003, several months after the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, I listened to radio reports on the beginning of the grim American occupation of that land from a tent on Denali while volunteering with the Park Service. It was there as well, strangely enough, that I first felt the pull of Iraq — or rather of the gaping void in the mainstream media when it came to what that occupation was doing to the Iraqi people. I then decided to travel from ice to heat, from Denali to the Middle East, to find out what was happening there and report on it.

That strange mountainside call led me into a career in journalism that pulled me away from my beloved Alaska whose vastnesses, largely devoid of a human presence, I’ve never experienced elsewhere. And as far as I traveled from its unique landscape, the feeling that the climate was already being disrupted in dramatic ways there stuck with me through my years of war reporting. The thought of the ever-receding glaciers in my former home state pained me and somehow drew me from America’s forever wars to another kind of war — on the planet itself — and into nearly a decade of climate reporting.

I told the audience all of this, occasionally pausing so as not to cry again thanks to a sadness born in part from the convulsions of wildfires, droughts, rapidly thawing permafrost, native coastal villages melting into the seas, and fast-shrinking glaciers. And don’t forget a Trumpian lapdog of a governor who, just like his darling president, seems unable to cut services fast enough or work hard enough to open yet more of this great state to drilling, logging, and pollution (despite his growing unpopularity).

The evening before, November 20th, I’d spoken at the University of Alaska in Anchorage and it was 48 degrees Fahrenheit (and raining, not snowing), a full 20 degrees warmer than the normal high temperature for that month. And that’s a reality that has become ever more the new normal there, even though the top third of the state lies inside the Arctic Circle. That, in turn, reflects another new reality: “Arctic amplification,” which means that the higher latitudes of this planet are warming roughly twice as fast as the mid-latitudes. In other words, Alaska is in the crosshairs of climate disruption.

Put another way, the audiences I was speaking to that month and all of my friends in Alaska are now living in what feels like a chronic state of shock as things unravel in their state at warp speed.

Alaska, the New Norm

It’s no secret that vast numbers of climate scientists are now grieving for the planet and humanity’s future, with some even describing their symptoms as a climate-change version of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD. Several of the scientists I interviewed for my book said as much. Dan Fagre, who works for the United States Geological Survey at Glacier National Park, was typical. When I asked him what he felt like while watching the glaciers (for which that park was named) disappear — they are expected to be gone by 2030 — he responded, “It’s like being a battle-hardened soldier, but on a philosophical basis, it’s tough to watch the thing you study disappear.”

And it’s not just climate scientists like him. Others living near areas where the changes are happening most dramatically seem to be experiencing such symptoms as well. “You wouldn’t believe what it was like to be in Anchorage last summer,” my friend Matt Rafferty told me when we met in that city on the morning I returned from Homer. “We saw 90 degrees on July 4th and then, later in the summer, the wildfire smoke was so thick on some days you literally could not see across the street downtown.”

An environmentalist who has long been working to protect Alaska from the extraction vultures, Matt is, like me, in love with the natural beauty of the place. I’ve traveled with him to the remote Alaskan backcountry and think of him as upbeat and indefatigable when it comes to his work, whatever the odds of success. But listening to him describe the climate convulsions wracking his home state recently, I couldn’t help but think of interviews I had done with family members in Iraq who had lost loved ones to U.S. military attacks. People with PTSD — and I know this from my own personal experience with it — tend to repetitively tell stories about the trauma they’ve experienced. It’s our way of trying to process it.

And this was exactly what Matt, normally not a guy given to overemphasis, was doing that morning, which shocked me. “We had rivers in south-central Alaska that were so warm the salmon were dying of heart attacks,” he continued, barely stopping to take a breath. “The river water reached 80 degrees in some of them! The water was 80 degrees! Can you believe that? There were literally tens of thousands of dead salmon floating belly up in many of the rivers. I did a pack-raft trip in the Talkeetna Mountains wearing nothing but a t-shirt and shorts! That is absurd! You know how cold the water usually is in the rivers here. It literally got so hot in the sun we had to pull out and sit underneath a tree in the shade!”

He recounted much that I already knew, including that Arctic sea ice had melted away at record speed and that, by the fall, permafrost was thawing at rates not predicted for another 70 years. On the coast of the Arctic Ocean in northern Alaska, whaling towns that traditionally used permafrost cellars to store, age, and keep their subsistence food cool throughout the year — the Inupiat use them for tons of whale and walrus meat — now find them pooling with water and sprouting mold thanks to the thawing permafrost.

By that September, Matt told me, he was struggling with depression. “I lost all hope, as it truly felt apocalyptic here,” he continued more slowly and quietly now, rubbing one of his arms in what I imagined was a sort of self-consoling gesture. Spending more time meditating, doing yoga, and finding helpful spiritual podcasts has, he added, become mandatory for him — and he’s far from alone in that among Alaskans as southern weather is visibly migrating north.

That day in Anchorage, I stopped at my favorite bookstore to check out the latest volumes on the state. One of them, Alone at the Top: Climbing Denali in the Dead of Winter, caught my eye. Arctic explorer Lonnie Dupre had made history in 2015 by summiting Denali in January… solo. It was an incredible feat that he writes about in his book, but the moment I won’t forget was when he described being trapped in his tent on that mountain at 11,200 feet during a storm that raged for days. At one point, he heard what sounded like small rocks pelting the tent, unzipped the door, poked his head out, and was shocked to find that, on December 31st, it was sleeting, not snowing. We’re talking about a moment when the average temperature for that elevation should have been something like 35 degrees below zero.

It hurt my heart to know that such weather paroxysms were afflicting even Denali, a mountain, standing so high and so near the Arctic Circle, that changed my life by drawing me to Alaska when I was in my twenties. Despite everything I now know, it still stunned me.

And here I am, like my close friends in that state, telling this story to anyone who will listen. I know this will sound over the top to non-Alaskan readers, but even writing this brings tears to my eyes. It’s simply not supposed to be this way. Just about nothing that’s happening there, climatologically speaking, today is what we once would have thought of as “natural,” even though it’s now the new norm.

Hearing so many of these stories while visiting proved too much to take in, as did knowing what’s now starting to happen to salmon, bears, moose, and other wildlife of all sorts. Thanks to chaotic climatic shifts, such creatures are beginning to migrate from what once were their home territories due to lack of familiar food. And all of it is, in its own way, traumatizing.

During a recent lecture at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, presented a grim overview of radically changed conditions across our northernmost state. In his 30 years with the National Weather Service in Alaska, Thoman has watched as the climate in his home state was disrupted by the anthropogenic climate crisis. Originally from Pennsylvania, he told the audience how reading about such a different world in works that ranged from Jack London’s turn-of-the-twentieth-century short story “To Build a Fire” to Barry Lopez’s book Arctic Dreams had led him to Alaska. London, for instance, had written about a place in which minus 70 degree temperatures were part of everyday life. “But the fact of the matter is,” he told us grimly, “the environment described in these books doesn’t exist anymore.” He added, “That’s really hard. But it’s what we’ve got, it’s what we live in.”

Thoman spoke of how, thanks to radically warming waters, the Bering Sea is literally experiencing a mass exodus of marine life, while the state itself is, like a beloved friend, in the midst of a health crisis that no one in power is truly trying to treat.

No wonder all of this leaves me with a feeling of utter impotence. Each new weather shock feels like another body blow. Or yet further evidence of how I’m losing a loved one. Alaska, in other words, is suffering climate death by a thousand cuts, while I struggle daily to accept the new reality: that the state is already irreparably changed.

Rainbow Peak

Deep waves of love and sadness had already begun coursing through me as my flight descended into Anchorage when this trip began. And such feelings only continued during the time I spent there. Time with old climbing buddies proved bittersweet, as it was never long before we couldn’t help but speak of the changes already occurring, even as we planned future forays into Alaska’s mountains.

The last full day, I knew I needed to be alone in those mountains. I’d brought the necessary gear with me for late-November hiking temperatures, or at least for the way I remembered them from the years when I lived there: crampons, an ice axe, extra layers of warm clothing for deep snow and mountain temperatures that should have been in the teens (even without taking the wind-chill factor into account).

Before sunrise that day, I headed south from Anchorage on the Seward highway as it dropped down beside the waters of Turnagain Arm. I was heading for a trail that would take me into the Chugach Mountains, one of my old stomping grounds.

Delicate pastel blues and soft buttery yellows illuminated the sky ahead as the lazy winter sun rose. While snow still covered the tops of the surrounding mountains, lower down the colors on them faded from bright whites to browns and greens — hardly a surprise, since temperatures here have been so warm and snow so scarce in this year’s disrupted lead-up to winter.

I passed several areas where, in the mid-1990s, I would already have been ice-climbing atop frozen waterfalls at this time of year. Now, they were visibly bone dry with temperatures too warm for ice to form.

After arriving at my trailhead, I hiked alone toward a nearby peak. Out of habit, I began with a heavy jacket on, but soon removed it, along with my gloves, in temperatures well above freezing. I wasn’t used to this and it felt abidingly strange to alter my old habits as I climbed.

I gained elevation quickly. Within a couple of hours, I was in something that finally seemed Alaskan to me, genuine winter conditions as I post-holed through the snow — which means having your legs regularly break through the surface snow to perhaps knee- or mid-thigh-height — making my way toward the summit. I paused from time to time to breathe in the smell of the trees and watch the occasional snow flurry flutter down into the valley below.

The summit ridge was blanketed in snow. As I arrived there, I suddenly realized that I had been chasing winter — that is, my own past life and dreams — up these mountains on this last full day of my visit, seeking to find an Alaska that no longer was.

I marveled at the grand 360-degree view, taking photos of the snowy peaks around me, drinking it all in, before I had to descend and head back to my home in Washington State and back to a climate-changed present on a burning planet where I would continue to dream of the Alaska I had once known. I knew I would be planning future ascents here, while at least some of it remains as it once was.

Shortly before boarding my flight home from the Anchorage airport, the cloud cover to the north cleared, revealing Denali’s still majestic white silhouette against a dark blue backdrop. I stood there, transfixed, for nearly half an hour unable to take my eyes off that mountain. Only when it began to grow dark and Denali was no longer visible could I allow myself to walk off, even as I wiped away more tears.

Dahr Jamail, a TomDispatch regular, is a recipient of numerous honors, including the Martha Gellhorn Award for Journalism for his work in Iraq and a 2018 Izzy Award for Outstanding Achievement in Independent Media. His newest book, The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption, was published this year. He is also the author of Beyond the Green Zone and The Will to Resist.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Originally published in TomDispatch.com

Copyright 2019 Dahr Jamail

Hundreds of journalists around the world sign open letter demanding freedom for Assange

by Oscar Grenfell

Hundreds of journalists and

media workers from every corner of the globe have put their name to an impassioned open letter demanding the unconditional freedom of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and an immediate “end to the legal campaign being waged against him for the crime of revealing war crimes.”

The Effect of the Sanctions: Is Iran Cracking Down Under the Strain?

by Ugo Bardi

But what if the sanctions had a true evil purpose in the sense of having the task of pushing Iran to do something stupid, as it was the case with Italy, long ago? Under heavy strain, Iranians could decide that their best bet is for a strong leader who would “Make Iran Great Again.” And what happens if things really go from bad to worse? Iranians could go through the same chain of misperceptions that Italy followed, bolstered by some local success, and becoming convinced to be a great power. Then, we all know that if an

American president wants to obliterate Iran with a nuclear strike, who or what could stop her? Then, if evil has to be, could that be the real purpose of the sanctions?

Paranoias of Interference: Russia, Reddit and the British Election

by Dr Binoy Kampmark

https://countercurrents.org/2019/12/paranoias-of-interference-russia-reddit-and-the-british-election

Russia baiting, at some level, serves the purpose of pre-empting votes and altering elections which may have very little to do with actual Russian influence. Even when such influence yields information that is hard to impeach, the fact that it issued from the actions of a foreign source, as it did in the 2016 US elections, is a sore point. Be it the NHS or Hillary Clinton’s true political colours, electors were not entitled to know. The issue of evidence remains less relevant than the acceptance by parties that this is happening. The result is magnification and paranoia, and a very bargain price method of making policy.

Zombie NATO Is Obsolete; Militarists Try To Retrieve It Through Expanded Targets

By Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) held an abbreviated two-day meeting this week in London on its 70th anniversary. On display was a zombie alliance that is bitterly divided on multiple issues and has lost its purpose for existing. Rather than recognizing it is time to end this obsolete military alliance, they decided to expand their activities, search for a purpose and conduct a study to determine their strategy.

By Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) held an abbreviated two-day meeting this week in London on its 70th anniversary. On display was a zombie alliance that is bitterly divided on multiple issues and has lost its purpose for existing. Rather than recognizing it is time to end this obsolete military alliance, they decided to expand their activities, search for a purpose and conduct a study to determine their strategy.

NATO is a cold war relic, an anti-Soviet tool continuing to exist 40 years after the Soviet Union ended. NATO was not formed to combat the Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact, which was created in 1955, although that was the previous excuse used for its existence. After the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the US began building an arsenal of nuclear weapons. A month after the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon in 1949, NATO was founded with 12 members. And the nuclear arms race took off.

When President Trump campaigned for office he correctly declared NATO was obsolete, but then he reversed course in April 2017. As president, he has pressured the 29 member-countries to increase their military spending. Between 2016 and 2020, NATO’s budget increased by $130 billion – twice as much as Russia’s total annual military spending. NATO members are expected to contribute two percent of their gross domestic product to the military. NATO’s total budget is 20 times that of Russia and five times that of China.

It is time for the US to withdraw from NATO and for the alliance to disband. It serves no useful purpose and is a cause of global conflicts and militarism.

NATO meeting, President Donald Trump, right, and President Emmanuel Macron on March 3, 2019. Credit Al Drago for The New York Times.

Internal Conflicts: An Alliance That Cannot Agree On The Definition Of Terrorism

NATO shortened its summit because internal divisions threatened to blow up the meeting.

On December 3, before the meeting, Trump and French President Emanuel Macron held a testy joint press conference. Macron told The Economist last month that NATO was suffering “brain death” because of the poor US leadership under Trump. Trump called Macron’s comments “very insulting” and “very, very nasty.” Macron and Trump are also at odds over Trump’s handling of the military conflict between Turkey and Syria, what to do with captured foreign Islamic State fighters and a trade dispute.

A late Tuesday video showed world leaders ridiculing Trump at the summit. Trump abandoned plans for a Wednesday news conference and branded the Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, “two-faced.” He cut short his attendance at the summit avoiding the final press conference.

While combating terrorism is one of NATO’s supposed tasks, Macron said: “I’m sorry to say that we don’t have the same definition of terrorism around the table.” Macron warned that “not all clarifications were obtained and not all ambiguities were resolved”. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to hold up efforts to protect the Baltics against Russia unless the alliance branded the Kurdish militias as “terrorists.” He later backed off and allowed NATO to go forward with increasing battalions on Russia’s borders to “protect Poland and the Baltic region” against fanciful threats from Russia.

NATO is facing four crisis areas. First, a deep political crisis including quarrels among the leading military members, accusations, and substantial differences of strategy and purpose. There is also a legal crisis as it consistently operates outside – indeed in violation of – its own goals and purposes and in violation of the United Nations Charter. Third, a moral crisis resulting from its wars against Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria…all catastrophes that caused unspeakable suffering, death, and destruction to millions. And, finally, an intellectual crisis, as an echo chamber alliance that sings only one tune: There are new threats, we must arm more, we need new and better weapons and we must increase military expenditures.

NATO’s Search For A Purpose

Rather than facing the fact that they are no longer serving a useful purpose, and despite their internal conflicts, NATO leaders did manage to pull together a final declaration.

Their declaration pointed the way to NATO expanding its military forces on a global scale that will result in creating instability and military conflicts to justify their existence. NATO has a history of brutal military attacks, including the brutal bombing and destruction of the former Yugoslavia and the Balkans in the late 1990s, regime-change wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, where it still has troops. And, the destruction of Libya that has left the country in chaos. NATO also worked with the United States in the violent coup in Ukraine in 2014.

NATO is playing its role as a military force that supports the US national security agenda. It continues to target Russia as “a threat to Euro-Atlantic security.” In reality, NATO creates that conflict by expanding eastward and putting weapons, bases, and troops along the Russian border. This violated a promise made by Secretary of State James Baker to the final Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. In a February 1990 meeting, Baker said three times that NATO would not expand, “not one inch eastward.” NATO’s expansion has been a major provocation in generating the New Cold War with Russia.

NATO is planning Defender 2020 the third-largest military exercise in Europe since the Cold War ended. Some 37,000 troops from 15 NATO nations will be involved including some 20,000 US troops who will be flown from their bases in the United States. Scott Ritter points out the costs associated with these exercises against Russia are considerable, along with the cost of raising, training, equipping and maintaining forces in the high state of readiness needed for short-notice response to an imagined attack by Russia. This is part of increasing confrontations along Russia’s borders, where a total of 102 NATO exercises were held in 2019.

Earlier this month, NATO said they’d formally rejected a Russian request to prohibit installing missiles previously banned under the now-defunct Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in Europe. The Russian request was made directly by President Putin, who fears “a new arms race” following both Moscow and Washington pulling out of the landmark 1988 INF treaty. Despite the facts, NATO blames Russia for the demise of the INF treaty. The French president brought out the reality: “Today would everyone around the table define Russia as an enemy? I do not think so.”

At this year’s summit, the NATO leaders “for the first time” discussed China as a collective security challenge. Prior to the meeting, CNN reported that NATO was falling in line with the anti-China strategy of the United States as NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg said the alliance needed to start taking into account that China is coming closer to us.’” He pointed to China “‘in the Arctic, … Africa, … investing heavily in European infrastructure and of course investing in cyberspace.”

Despite Stollenberg’s push to make China a target of NATO, their members could only agree on a declaration that said: “China’s growing influence and international policies present both opportunities and challenges.” NATO members know that China is a benefit to the economy of their nations and that the Belt and Road Initiative connecting China to Europe through the Middle East and Africa is likely to be the defining source of economic growth this century.

NATO has also joined President Trump’s call for the militarization of space, declaring “space an operational domain for NATO” in their declaration. Related to this, they also pledged to increase their “tools to respond to cyber attacks.”

In April we reported that NATO seeks to expand to Georgia, Macedonia and Ukraine as well as spreading into Latin America with Colombia joining as a partner and Brazil considering participation (not coincidentally, these two nations border Venezuela).

NATO is also bringing nuclear weapons to the Russian border. The Washington Post reported, “A recently released — and subsequently deleted — document published by a NATO-affiliated body has sparked headlines in Europe with an apparent confirmation of a long-held open secret: some 150 US nuclear weapons are being stored in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey.” Raising questions: Under whose control are these weapons held? Are host countries permitted access to US nuclear weapons? Are the host nations informed? Do NATO’s practice deployments involve nuclear bombs and missiles? The Brussels Times reported this summer that “In the context of NATO, the United States [has deployed] around 150 nuclear weapons in Europe.”

NATO’s search for a purpose has led to a fundamental strategic review of the alliance’s purpose. Members know their mission is unclear and their purpose is questionable.

70 Years Of Destruction Is Enough, Time To End NATO

The 70th anniversary of NATO is an opportunity to honestly examine the history of NATO destabilization, wasteful military spending, and destructive military attacks. It is also an opportunity for people to urge the end of NATO. On April 4, 2019, NATO foreign ministers met in Washington, DC to celebrate its 70th anniversary, peace and justice activists held a week of actions in protest, disrupting meetings, shutting down an entrance to the State Department and taking the streets. This past week there was a large anti-NATO protest in London.

Scott Ritter believes NATO is as good as dead writing “NATO is on life-support, and Europe is being asked to foot the bill to keep breathing life into an increasingly moribund alliance whose brain death is readily recognized, but rarely acknowledged.”

Ajamu Baraka of Black Alliance for Peace declares: “Today [NATO] is the militarized arm of the declining but still dangerous Pan- European Colonial/capitalist project, a project that has concluded that the stabilization of the world capitalist system and continued dominance of U.S. and Western capital can only be realized through the use of force.”

It is time to demand an end to this destructive alliance as a step toward ending white supremacy, colonization, the destructive military-industrial complex, and the exploitative capitalist economy.

Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers are directors of Popular Resistance

Stand up and fight

by Bhuwan Thapaliya

It’s time to stand up

and fight with the system.

Stand up and fight.

Stand up and fight.

No comments:

Post a Comment