U.S. Navy heading into cover-up mode in collision of the USS Fitzgerald

U.S. Navy sources report to WMR that the Navy is heading into familiar cover-up mode in the official investigation of the collision of the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) with the ACX Crystal, a Philippines-flagged container ship manned by a Filipino crew of 20. The collision, which killed seven U.S. Navy sailors who drowned in a flooded below-water line berthing compartment, took place near Japan’s Izu Peninsula on June 17 at 2:20 a.m. local time. The Crystal was under charter to a Japanese firm, Nippon Yusen KK (NYK), and was en route from Nagoya to Tokyo. The Crystal’s registration holder is Sinbanali Shipping, Inc. based in Manila, and its actual owner is Dainichi-Invest Corporation of Kobe, Japan.

The Navy’s investigation of the incident is headed by Rear Admiral Brian Fort, a Navy nuclear power-trained surface warfare officer. The Fitzgerald is not nuclear powered but driven by four gas turbine engines.

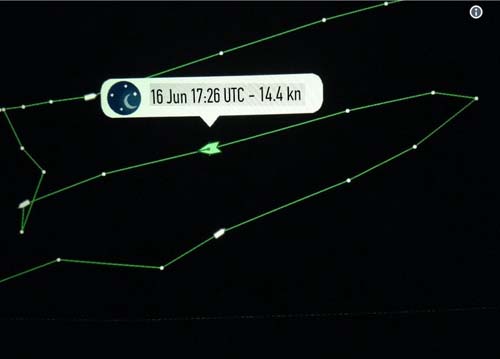

Significant questions have been raised internally within the U.S. Navy about the Crystal’s pre-collision series of bizarre maneuvers, including “corkscrew” turns. Such maneuvers are practically unheard of for merchant vessels, particularly container ships, which follow direct routes in order to save time and money. After the odd series of turns, the Crystal struck the Fitzgerald amidships.

The Crystal waited for almost an entire hour before it reported the collision to the Japanese Coast Guard, a factor that may have led to the seven fatalities aboard the Fitzgerald. The Crystal, which was heading east toward Tokyo from Nagoya, turned around off the Izu Peninsula, completing a full circle, before making a sharp right turn and striking the Fitzgerald. Plainly put, the container ship, which is three times the size of the Fitzgerald, appears to have turned around purposely in order to collide with the Navy destroyer.

There is also the curious fact that the Crystal engaged in approximately the same circle pattern before making the same series of turns just prior to colliding with the Fitzgerald. It is as if the Crystal was making a dry run test some 45 nautical miles to the west of the impact point before making the actual fatal right turn into the Fitzgerald.

The Japanese Coast Guard first reported that a distress call came from the Crystal at 2:25 a.m., five minutes after the Crystal’s automated system recorded the 2:20 collision. However, the Crystal, which was operating on automatic pilot, actually struck the Fitzgerald at 1:30 a.m., and did not report the collision until 2:25 a.m., almost an hour after the Crystal’s bow plowed through the starboard side of the Fitzgerald. The U.S. Navy 7th Fleet, the parent command for the Fitzgerald, recorded the collision at 2:20, putting the Navy in disagreement with the crew members of the Crystal who were interviewed by the Japanese Coast Guard after the incident.

The Crystal’s charter company, NYK, reports the collision occurred at 1:30 a.m. and the Japanese Coast Guard has come around to agree with that as the time of the incident. The commander of the 7th Fleet, Vice Admiral Joseph Aucoin, has offered no explanation for the 50 minute time discrepancy for the collision between the Crystal’s crew, NYK, and the Japanese Coast Guard and the Navy. There is also the curious event of President Trump waiting two entire days before tweeting his condolences to the families of the drowned Navy sailors.

Several questions will dominate the Navy’s investigation. First, why was the Crystal navigating on unsupervised autopilot in one of the busiest shipping channels in the world? Why did the Fitzgerald’s state-of-the-art combat information center, in addition to the bridge watch section, not detect the presence of a ship three times the destroyer’s size? Why didn’t the starboard lookout on board the Fitzgerald detect that his ship was in extremis from the well-known danger signals of a vessel on a constant bearing with decreasing range? Why did the Fitzgerald not know of the Crystal’s close proximity via the container ship’s Automatic Identification System’s (AIS) repeated VHF radio transmissions? Although U.S. Navy ships have similar AIS systems, they often disable them when on sensitive missions. However, Navy ships routinely turn on their AIS systems when under the control systems of local vessel tracking services (VTS), such as the Tokyo Bay VTS. AIS systems are installed on some 400,000 ships, navigation buoys, lighthouses, and offshore oil drilling platforms around the world. If the Fitzgerald’s AIS was activated, there should have been a warning on both vessels of the Crystal’s close proximity. The Crystal’s AIS was squawking its location at the time of the collision, as evidenced by its track being transmitted to various websites, including Marinetraffic.com.

Two U.S. Navy navigational incidents in five months in Tokyo Bay have Navy officials concerned about maritime cyber-hijacking. Top: USS Fitzgerald after collision with container vessel. Bottom: USS Antietam after running aground in Tokyo Bay in January 2017.

In January of this year, the Navy’s Ticonderoga class cruiser USS Antietam (CG-54) ran aground in Tokyo harbor, near the Navy facility at Yokosuka. The cause of the incident, which resulted in a leak of 1,100 gallons of hydraulic oil, but no injuries, remains as murky as the collision outside of Tokyo harbor between the Fitzgerald and Crystal.

There is one scenario that has some Navy officials extremely alarmed. They fear that the Crystal may have fallen victim to maritime cyber-hijacking of its Automatic Identification System and Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS). Some “white hat” hackers have previously hacked AIS systems, causing them to cease broadcasting their locations. In some cases, hackers corrupting an AIS system managed to have a tug boat disappear from the Mississippi River. Not only did the tug disappear, but the hackers manipulated the AIS data to have it reappear on a lake in downtown Dallas, Texas. ECDIS, which replaces paper nautical charts, can also be hacked because its components of AIS, Navtex (navigational telex), radar, and depth sounders are all vulnerable to data manipulation. The satellite-based Global Positioning System (GPS) has fallen victim to similar cyber-hacking attacks.

Although the U.S. intelligence community would rather not reveal the extent of the vulnerability of ships to cyber-hijacking on the high seas, it is believed that among the nations that possess such a capability are North Korea, China, Taiwan, South Korea, Iran, Israel, Australia, India, and the United Kingdom. Even pirates based in Somalia have shown an interest in cyber-hacking to support their plunder on the high seas.

The Crystal’s crew was reportedly asleep during the ship’s odd turning patterns and the autopilot’s warning system appears to have been disabled. However, the hacking of the Crystal’s navigation system does not explain the failure of the Fitzgerald to detect the container ship, unless the Fitzgerald’s combat information center, including navigation and radar systems, also came under a cyber-attack. If the vessels fell victim to a simultaneous cyber-attack and there was any intelligence pointing in that direction, it would explain why the White House waited two full days to comment on the incident and send condolences, albeit via Twitter, to the victims’ families.

A White House that thrives on a lack of transparency, coupled with the Navy’s long tradition of obfuscation and faulty investigations into such incidents as the June 1967 Israeli attack on the USS Liberty, the July flight deck fire on board the USS Forrestal, the sinking of the submarine USS Scorpion in 1968, the 1989 explosion of a gun turret on the USS Iowa, the 2000 terrorist attack in Aden harbor on the USS Cole, the January 2001 collision between the submarine USS Greenville and Japanese fishing trawler Ehime Maru, and countless others, will likely result in the real reason for the Fitzgerald-Crystal collision ever being revealed.

Previously published in the Wayne Madsen Report.

Copyright © 2017 WayneMadenReport.com

Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative journalist and nationally-distributed columnist. He is the editor and publisher of the Wayne Madsen Report (subscription required).

http://www.intrepidreport.com/archives/21574

No comments:

Post a Comment